Building game experiences for virtual reality is incredibly difficult. It’s even more difficult when they have a tendency to make you ill.

“I’m super sensitive to simulation sickness,” says Nick Donaldson, level designer at Epic Games. “Super, super sensitive. I wear the Oculus headsets more than anyone else here, and as soon as something weird happens —”

He makes a throwing motion, pushing an invisible visor off his face and pretending to retch.

“There’s a bucket we keep by his desk,” says Alan Willard, Epic’s senior technical artist sitting at his elbow.

Donaldson’s sensitivity to motion isn’t uncommon. Less common is a sensitivity to frame rate, but it’s just as dangerous. A console generation ago audiences were satisfied with 30 frames per second. Now it’s 60, and later this year, when the retail Oculus headset goes on sale, its standard will need to be closer to 90.

Donaldson works on the Unreal Engine, which regularly boasts about its state of the art, photo-real graphics and often lives up to those claims. Pulling 90 frames per second, while living up to the promise of that engine, is challenging even on a good day. Other days, it can feel impossible.

“Developing for VR at the moment, because it’s still the early days, is brutal,” Donaldson says. “The hardware we’re working with is only linearly increasing [in power] rather than exponentially, like the requirements are. And then as soon as you mess something up — you drop a frame — it makes people sick.”

“Developing for VR at the moment, because it’s still the early days, is brutal,” Donaldson says. “The hardware we’re working with is only linearly increasing [in power] rather than exponentially, like the requirements are. And then as soon as you mess something up — you drop a frame — it makes people sick.”

And yet Donaldson is passionate about VR. Turns out, he’s a kind of game design masochist. Who better to turn to for the latest and greatest demonstration of the Unreal Engine?

Donaldson’s tech demo, called Showdown, impressed critics several times from behind closed doors late last year. Polygon is able to share more of it on video today. But soon everyone who works in Unreal will have access to the guts of this single, short level as a free download for the Unreal Engine. And everyone will be able to experience it in VR with the help of the Oculus Rift.

Along with Showdown will come all the new tricks that the team at Epic have been working on to help bring about the future of VR. Epic hopes that maybe, just maybe, between the engine itself and the knowledge of designers like Donaldson who can push it to its limits, Epic will enable someone, somewhere to make the first great VR game.

“The goal for Showdown,” Donaldson says, “is that Oculus had their newest prototype called Crescent Bay on the way. It was the first time that Oculus had been 90 hertz, as opposed to 75 for the previous version. The resolution was much higher, the optics were great and the motion tracking was much, much better than the Development Kit 2.

“Oculus wanted a big wow, something with as much visual impact as humanly possible. … And we only had five weeks to make it.”

Where most games are made from scratch, Donaldson had to build a demo from spare parts lying around the office. He also didn’t have a lot of personnel to work with. Epic gave him one artist, so together they began raiding past Epic demos for assets and animations.

“Right now working in VR is all about picking your battles,” Donaldson says. “It was really tough [making Showdown]. To start with I didn’t really know how the fuck this was going to work. How? Because, a scene like what we envisioned in Showdown, with [lots of] stuff happening, with nice lighting on everything and little shadows all over the place, there’s no way to actually make that run properly in VR — unless you are amazingly aggressive about picking the really important things.

A 2013 Epic tech demo called Infiltrator caught his eye, and he figured he could borrow some assets. If you look closely at the Infiltrator video below, you can see the soldiers he repurposed as futuristic cops in Showdown.

The trouble is, the motion capture information Donaldson had wasn’t made for VR. It wasn’t even really made for a game experience. Each individual capture was custom made for the Infiltrator cinematic, and at the top of the spectrum they were only about six seconds long.

So, Donaldson thought, what if he made Showdown run in slow motion? Six seconds, when slowed down, would be just enough to get the job done and let his team focus on the fidelity in the rest of the scene.

With the soldiers in place, and the robot as well as the street scene borrowed from another demo called Samaritan, Donaldson needed light. Lighting a scene, he explains, is one of the most demanding things you can do in a modern game engine.

Getting to 90 frames per second wouldn’t be easy.

“I couldn’t have just thrown it in there and made it all work just by default,” Donaldson says. “We had to pick all of our battles really specifically.

“We had to make sure there were no shadow-casting lights. All those shadows that you see in there were faked. The lighting was very specifically all indirect, diffused lighting. It was all hitting the building and then bouncing over the scene because it’s a lot easier to make those kinds of shadows look real.”

Donaldson worked up a system whereby the size of each soldier’s shadow would change based on the distance of their foot from the ground. They’re not being made by the light in the frame; they’re being made by a bit of code he stuck to each character’s feet. It’s a process that’s a lot less expensive, from a hardware perspective, and leaves more resources available to drive all the physics objects that go sailing around the scene.

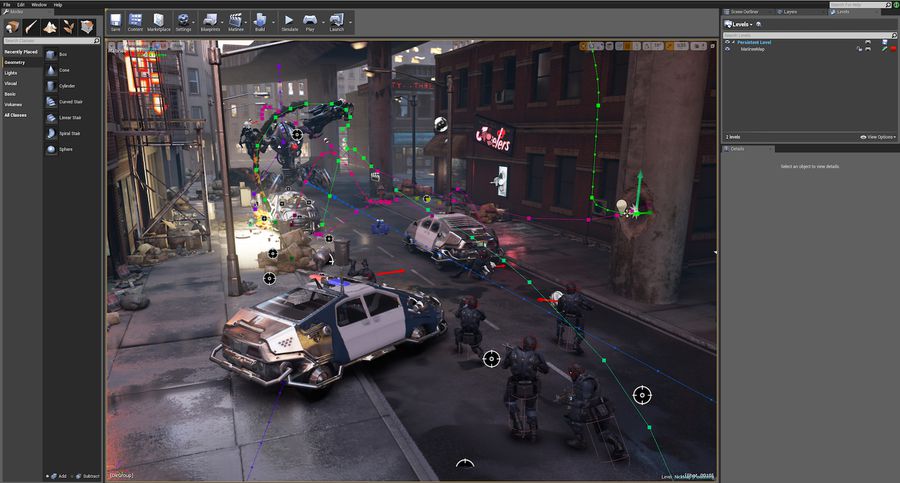

In fact, if you get inside the Unreal engine and zoom in close to the shadow beneath the police car, you can see it’s little more than a sticker. Get too close and it disappears entirely.

But from the perspective of the person experiencing it in VR, Showdown looks seamless. Raise that camera up, over the scene to look down on it from above, and it looks a lot like an old-school Hollywood backlot. Each storefront is paper thin, and every alleyway is a dead end leading off into misty gray nothingness.

Showdown is an incredible achievement, but it’s not a game. It’s not even a game level, because it’s not a truly interactive experience. It’s a theme park ride that looks great from just this one perspective. Change the viewing angle, and the illusion breaks down.

The fact is that Showdown is on rails for the simple reason that Donaldson doesn’t have the hardware to run it any other way. And that hardware doesn’t exist yet.

But in the near future of VR, the player could be given more control than Showdown allows. And it’s up to developers like Epic, and the manufacturers of the hardware their Unreal Engine runs on, to bridge the gap.